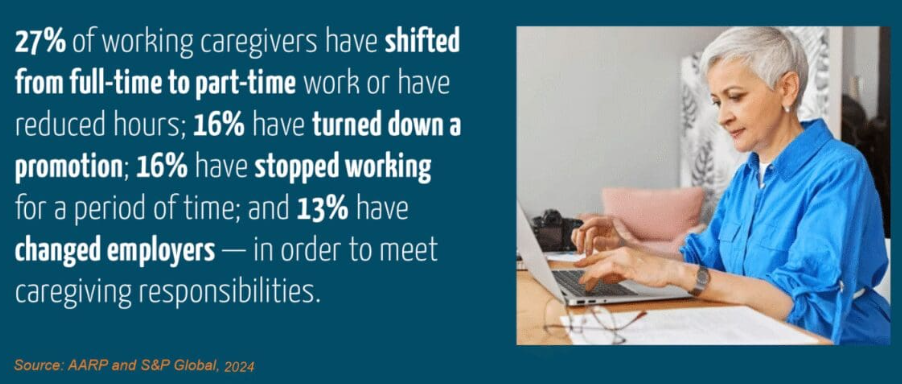

There are 65 million caregivers across the United States; the economic value of this unpaid work (lost income, decreased retirement savings, out-of-pocket expenses for medical and household needs) is estimated at over $600 billion annually, with women bearing a disproportionate share of both the time and financial cost

Taking Care of Yourself As a Caregiver

From 2015 to 2022, the prevalence of frequent mental distress increased among both caregivers and non-caregivers. Frequent mental distress and depression were more prevalent among caregivers when compared with non-caregivers. Measures for 13 of the 19 health indicators were unfavorable for caregivers when compared with non-caregivers. Four of the seven chronic physical conditions were more common among caregivers: obesity, asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and arthritis.

Caregiving is a huge responsibility that can be very rewarding, but it can take its toll. It’s not always obvious when a person needs help. Look out for these signs of caregiver stress:

- Feeling exhausted, overwhelmed, or anxious

- Becoming easily angered or impatient

- Feeling lonely or disconnected from others

- Having trouble sleeping or not getting enough sleep

- Feeling sad or hopeless, or losing interest in activities you used to enjoy

- Having frequent headaches, pain, or other physical problems

- Not having enough time to exercise or prepare healthy food for yourself

- Skipping showers or other personal care tasks such as brushing your teeth

- Misusing alcohol or drugs, including prescription medications

Making time for self-care is both difficult and critical to providing compassionate care. It can be difficult, especially when the strongest instinct is to put the care recipient above everything else. But that doesn’t fill (or refill) a caregiver’s bucket and ensure you’re able to provide the best possible care for your loved one. Self-care depends on personal preference but being outdoors, moving (e.g. yoga, exercise), time spent with others, participating in support groups, and listening to music have all been proven to be healing. These tips from Caring Bridge offer other ideas

- Take Care of YOU: There’s a reason flight attendants tell you to put your own mask on first…it’s because you can’t help anyone else if you’re compromised. So, give yourself permission to ask for a break. See your doctor. Take time to find joy every day. Rest and feed your body and soul.

- Take Help from Your People: When your friends, family or community offer support –accept it! When people offer to help you, they are sincere, so take them up on their offer. Have a list of things that need to be done. Accept a meal. When you feel like you’re overwhelmed, have someone come sit with your loved one for an hour or two. If someone offers to help, practice saying, “Thanks for asking.

- Be Realistic: It’s important, both as a new caregiver or an experienced one, to be realistic about what your loved one is experiencing and allow yourself to cope with feelings of sadness, and don’t be afraid to consult a professional for help if you need it.

- Be Open to New Methods of Care: Technology can be a great tool for helping care for your loved one. New programs, like online patient portals provide 24/7 access to personal health information and help doctor and patient/family communication.

Tips for Caregiving with More Confidence and Less Self-Doubt

People who initially hesitate to take over caregiving duties come to those roles in various ways. Some believe they have little choice but to assume the responsibility. For others, their hesitation stems from feelings of guilt and grief. Reluctant caregiving, sometimes referred to as no-choice caregiving, can develop from a profound sense of sadness or grief as caregivers watch their life circumstances change and feel overwhelmed about the prospect of managing someone else’s needs.

First, believe in your abilities and trust your gut. You might question your capability to handle your loved one’s complex needs. However, the unique bond and intimate knowledge you have of them is an invaluable asset. Trusting your instincts means more than just having faith in your decision-making; it’s about recognizing that you know what’s best for the person better than anyone else.

Caregiver education is one of the best tools to help understand the need for self-care and the signs of burnout. For caregivers to understand and overcome feelings of frustration, self-doubt, anger, guilt, and resentment, the first step is recognizing it’s normal to feel hesitant or reluctant, and setting boundaries early on helps prevent feelings of anger and frustration from escalating. Other valuable education includes:

- Counseling to offer essential help in managing these emotions, building effective coping strategies.

- Mastering proper techniques for physical tasks like lifting can prevent injuries and simplifying caregiving tasks.

- Embracing technology, apps (e.g. health management) and other tools that can enhance the person’s independence and reducing stress.

- Understanding how caregivers and care recipients’ abilities and needs change over time and the importance of being flexible and adaptable.

- Asking for things to be broken down into simpler explanations and tasks.

- Learning to communicate effectively with the team of people treating your loved one and ask questions until you understand. If you aren’t comfortable asking face-to-face, send a text or email with your request.

- Being honest about what you need and what you don’t need. Not every offer is going to be helpful.

Healthy Ways to Overcome Caregiver Burnout

“Knowing how to say when and ask for help is not failure. Failure is not asking for help.”

That message resonates deeply across caregiving communities—and for good reason. Caregivers who push themselves past their limits face serious risks: injury, illness, depression, anxiety, chronic disease, and even life-threatening burnout.

Unlike everyday stress, caregiver burnout often shows up as prolonged emotional numbness and disconnection. Experts warn that it can impair judgment, weaken the immune system, intensify fatigue, and ultimately jeopardize both caregivers and the loved ones they support. Some caregivers struggle to recognize they’re burning out because they’re consumed by the daily demands of care.

Caregivers often develop their own ways to manage intense emotions: yelling in the shower, punching a pillow, counting to 10, or even letting out a cathartic swear word in private. Research shows that swearing can help regulate emotions during extreme stress—what matters is releasing tension in a safe, contained way.

Many caregivers find support through therapy, guided meditation, journaling, or laughter yoga. Others protect their well-being by setting firm personal boundaries, choosing healthier coping habits, and carving out small daily moments of rest.

Support groups—online or in person—offer validation, practical advice, and the comfort of knowing you’re not alone. Caregivers consistently report that talking with others who “get it” is life-changing.

Regular respite care is also essential. Planned breaks allow caregivers to maintain balance, reconnect with themselves, and return more grounded and resilient. Resources such as the National Respite Locator can help caregivers find options in their area.

Burnout can look like exhaustion, pain, loss of empathy, or even moments of resentment. In the most severe cases, caregivers may experience thoughts of harming themselves or others—an urgent sign that they need immediate help. Signs of caregiver burnout can include:

Physical: chronic fatigue, sleep changes, weight shifts, frequent illness, aches, weakness

Emotional: anxiety, depression, hopelessness, irritability, suicidal thoughts

Cognitive: forgetfulness, difficulty making decisions

Behavioral: withdrawal, neglecting personal needs, increased substance use

Caregiving requires strength, compassion, and patience, but it shouldn’t cost caregivers their own health. Seeking support isn’t a weakness. It’s an act of courage, and one of the most important things a caregiver can do for themselves and the people they love.

At Trial

When someone has a brain injury, the whole family’s life changes, and it is important for jurors to understand caregiving isn’t just helping with a few tasks—it’s constant supervision, emotional support, and making sure the injured person stays safe. Brain injury survivors may look “okay” on the outside, but inside they’re struggling with memory problems, poor judgment, fatigue, mood swings, and difficulty handling everyday decisions. That means the caregiver has to stay alert around the clock.

Caregivers often give up their jobs, their sleep, their social lives, and their own health. They manage medications, appointments, transportation, finances, and crises—every single day. They watch for wandering, falls, impulsive behavior, or simple mistakes that can lead to real danger. It’s exhausting, and it takes a toll physically and emotionally.

This isn’t temporary and what they provide is not optional, it is essential. And if they cannot continue, the cost of replacing their care is enormous. A verdict is the only mechanism the law provides to make this family whole, and the award must recognize not only the harm done to the injured person, but the profound, lifelong burden placed on the caregiver.

Helpful Resource: The Family Caregiver Alliance

The FCA provides services to family caregivers of adults with physical and cognitive impairments. Their services include assessment, care planning, direct care skills, wellness programs, respite services, and legal/financial consultation vouchers. There are a lot of great resources on the site, such as the ‘Just in Time’ hospital tip sheets for family caregivers that offers helpful advice on how to communicate with hospital staff when the person you’re caring for needs surgery, is hospitalized or ends up in the Emergency Department.

Did You Know?

There is a Caregiver’s Bill of Rights? Here it is-

I have the right . . .

- To take care of myself. This is not an act of selfishness. It will give me the capacity to take better care of my relative.

- To seek help from others even though my relative may object. I recognize the limits of my own endurance and strength.

- To maintain facets of my own life that do not include the person I care for, just as I would if he or she were healthy. I know that I do everything that I reasonably can for this person, and I have the right to do some things for myself.

- To get angry, be depressed, and express other difficult feelings occasionally.

- To reject any attempt by my relative (either conscious or unconscious) to manipulate me through guilt, anger, or depression.

- To receive consideration, affection, forgiveness, and acceptance for what I do for my loved one for as long as I offer these qualities in return.

- To take pride in what I am accomplishing and to applaud the courage it has sometimes taken to meet the needs of my relative.

- To protect my individuality and my right to make a life for myself that will sustain me in the time when my relative no longer needs my full-time help.

- To expect and demand that as new strides are made in finding resources to aid physically and mentally impaired people, similar strides will be made toward aiding and supporting caregivers.